Hypothesis Testing Cheat Sheet

Basic Idea:

How to decide if it is reasonable to conclude that an

underlying true parameter (e.g. ![]() in a regression

model

in a regression

model ![]() ) is equal to a

particular value

) is equal to a

particular value ![]() on the basis of

an estimate

on the basis of

an estimate ![]()

We call this a hypothesis about ![]() and call it

the Null Hypothesis,

and call it

the Null Hypothesis,

H0: ![]() .

.

We also take note of what must be the case if H0 is not true. This is called the Alternative Hypothesis written as

H1: ![]()

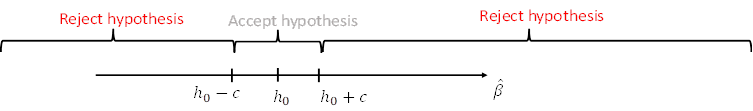

We will reject H0 (i.e. conclude that ![]() is probably

not equal to

is probably

not equal to ![]() ) if the

estimate

) if the

estimate ![]() is quite far

away from

is quite far

away from ![]() (i.e. if

(i.e. if ![]() is either much

bigger or much smaller than

is either much

bigger or much smaller than ![]() ).

).

But how far is too far exactly? Or in terms of the

figure above: how big is ![]() ?

This depends on the reliability of the estimate

?

This depends on the reliability of the estimate ![]() . If we know

that the estimate is imprecise – i.e. there is a high likelihood that

. If we know

that the estimate is imprecise – i.e. there is a high likelihood that ![]() is very far

away from

is very far

away from ![]() even if H0 is

true, then we would tolerate higher values for c.

even if H0 is

true, then we would tolerate higher values for c.

With the Monte-Carlo Analysis we have seen that

·

![]() is

(approximately) normally distributed

is

(approximately) normally distributed

·

The estimate is more precise (i.e. the standard error ![]() is smaller) if

the variance of the error (

is smaller) if

the variance of the error (![]() ) is smaller or

the variance of the explanatory variable x is larger.

) is smaller or

the variance of the explanatory variable x is larger.

After running a regression it is possible to estimate ![]() (i.e. we can

label this estimate

(i.e. we can

label this estimate ![]() ) and R

provides this estimate as part of its regression output. Here is an example:

) and R

provides this estimate as part of its regression output. Here is an example:

df=read_dta("../data/foreigners.dta")

df['crimesPc']=df$crimes11/df$pop11

reg1=lm(crimesPc~b_migr11,df)

summary(reg1)

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = crimesPc ~ b_migr11, data = df)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1.5886 -0.3789 -0.1038 0.2046 14.0988

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 0.992957 0.079387 12.508 < 2e-16 ***

## b_migr11 0.037630 0.005088 7.396 1.23e-12 ***

## ---

## ---

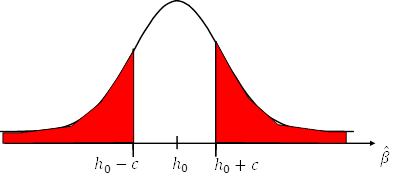

Hence, we can use the bell-shaped normal distribution (with

mean ![]() and standard

error

and standard

error ![]() ; i.e.

; i.e. ![]() ) to work out the

likelihood is for

) to work out the

likelihood is for ![]() to fall in the

rejection area even though it is true; i.e. it is the combined area under the

bell curve in the tails of the distribution for a given c.

to fall in the

rejection area even though it is true; i.e. it is the combined area under the

bell curve in the tails of the distribution for a given c.

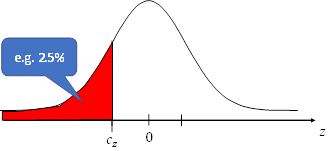

Equally we can work out which ![]() goes along

with a given desired probability. This latter approach is what we do in

hypothesis testing. We decide first what probability (i.e. risk that we reject

the hypothesis even though it is correct) we find acceptable (e.g. 1%, 5% or

10%) and we then work out the relevant c. Those risk levels are also referred

to as significance levels.

goes along

with a given desired probability. This latter approach is what we do in

hypothesis testing. We decide first what probability (i.e. risk that we reject

the hypothesis even though it is correct) we find acceptable (e.g. 1%, 5% or

10%) and we then work out the relevant c. Those risk levels are also referred

to as significance levels.

Implementation

It turns out that instead of working out the c for a given

distribution ![]() it’s sufficient

to work out the relevant threshold numbers only once for the Standard Normal

Distribution

it’s sufficient

to work out the relevant threshold numbers only once for the Standard Normal

Distribution ![]() . The reason

for this that an estimate that is Normally distributed can always be converted

into one that is Standard Normally distributed by subtracting its expected

value and dividing by its standard error; i.e. by computing

. The reason

for this that an estimate that is Normally distributed can always be converted

into one that is Standard Normally distributed by subtracting its expected

value and dividing by its standard error; i.e. by computing

![]()

Thus, we can compare ![]() to the

thresholds for the standard normal distribution. To find those in turn we can

use the qnorm() R-function which is the inverse of the cumulative density

function. You have to provide qnorm with a probability (e.g. 0.025) and it will

tell you for which value

to the

thresholds for the standard normal distribution. To find those in turn we can

use the qnorm() R-function which is the inverse of the cumulative density

function. You have to provide qnorm with a probability (e.g. 0.025) and it will

tell you for which value ![]() the left tail

of the normal distribution will correspond to that probability

the left tail

of the normal distribution will correspond to that probability

qnorm(0.025) = -1.959964

Similarly, we can find the thresholds for other possible significance levels

qnorm(0.005) = -2.575829 for 1%

qnorm(0.05) = -1.644854 for 10%

So if we find a ![]() =0.037630

(as in the example above) and

=0.037630

(as in the example above) and ![]() and we are testing the

hypothesis that

and we are testing the

hypothesis that ![]() could

be zero (H0:

could

be zero (H0: ![]() we need to

check if

we need to

check if ![]() is within the

interval implied by those values (i.e. in this case we would reject the

hypothesis even if we only allowed for a small significance level).

is within the

interval implied by those values (i.e. in this case we would reject the

hypothesis even if we only allowed for a small significance level).

What about t-statistics?

The so-called t statistic is like the z value above except that we now allow the standard error to be estimated as well:

![]()

Hence, because in practice we never know ![]() this is what we

compute in practice. As a consequence, rather than being Standard Normally distributed,

t is t distributed. Luckily this does not matter much in practice because the t

distribution is almost identical to the standard normal distribution, provided our

sample is large enough; e.g. at 12 observations the 5% threshold value would be

2.228. However, at 100 observations the threshold is -1.984467; i.e. fairly

close to the 1.96 found with the normal distribution. You can work this out

with the qt(0.025, 98) command where the second number refers to the degrees of

freedom; i.e. the number of observations minus the number of parameters in your

model (i.e. 2 in our case: intercept and slope).

this is what we

compute in practice. As a consequence, rather than being Standard Normally distributed,

t is t distributed. Luckily this does not matter much in practice because the t

distribution is almost identical to the standard normal distribution, provided our

sample is large enough; e.g. at 12 observations the 5% threshold value would be

2.228. However, at 100 observations the threshold is -1.984467; i.e. fairly

close to the 1.96 found with the normal distribution. You can work this out

with the qt(0.025, 98) command where the second number refers to the degrees of

freedom; i.e. the number of observations minus the number of parameters in your

model (i.e. 2 in our case: intercept and slope).

P-values

An even simpler way of doing the same thing (i.e. hypothesis

test) involves P values. In the past without computers this was hard but now this

is easy. P values for the hypothesis test H0: ![]() are routinely

reported along with regression output; e.g. in R it’s the values in the column Pr(>|t|).

are routinely

reported along with regression output; e.g. in R it’s the values in the column Pr(>|t|).

The P value is the significance level you would have to

choose if the value you estimated was equal to the rejection threshold; i.e. ![]() . Hence, thus

if P is very small (smaller than your desired significance level) then you

would reject the hypothesis. If it is rather large (larger than your desired

significance level) than you don’t reject your hypothesis.

. Hence, thus

if P is very small (smaller than your desired significance level) then you

would reject the hypothesis. If it is rather large (larger than your desired

significance level) than you don’t reject your hypothesis.

You can get P-values for tests other than H0: ![]() using the linearHypothesis

command (part of library(“car”)).

using the linearHypothesis

command (part of library(“car”)).

For example if you wanted to check if the migration coefficient in the example above is equal to 0.04 you could run the command

linearHypothesis(reg1, c( "b_migr11= 0.04") )

Hypothesis:

Hypothesis:

b_migr11 = 0.04

Model 1: restricted model

Model 2: crimesPc ~ b_migr11

Res.Df RSS Df Sum of Sq F Pr(>F)

1 323 301.53

2 322 301.33 1 0.20309 0.217 0.6416